Governments are using AI to make decisions. What should we do about it?

Also, I finished my Master's! ⚖️💻🧩

Disclaimer: The writing below represents my opinions, views, and thoughts. They are not a reflection of my employer.

So, guess who’s finished his Master’s degree? This guy!

I finally submitted my final paper last week and I’ve been enjoying the last few days just recovering and relaxing. Sleeping late, waking up late. Making grilled cheese sandwiches at 3am. Catching up on films and TV shows.

I have so much to say about finishing my MPP. There are not enough words to truly convey all I’m feeling - this weird mixture of pride, accomplishment, exhaustion, frustration. But I promise that I’ll write about that soon enough. I think I’ll need time to reflect on the last year and eventually sit down to write. Until then, I’m going on vacation!

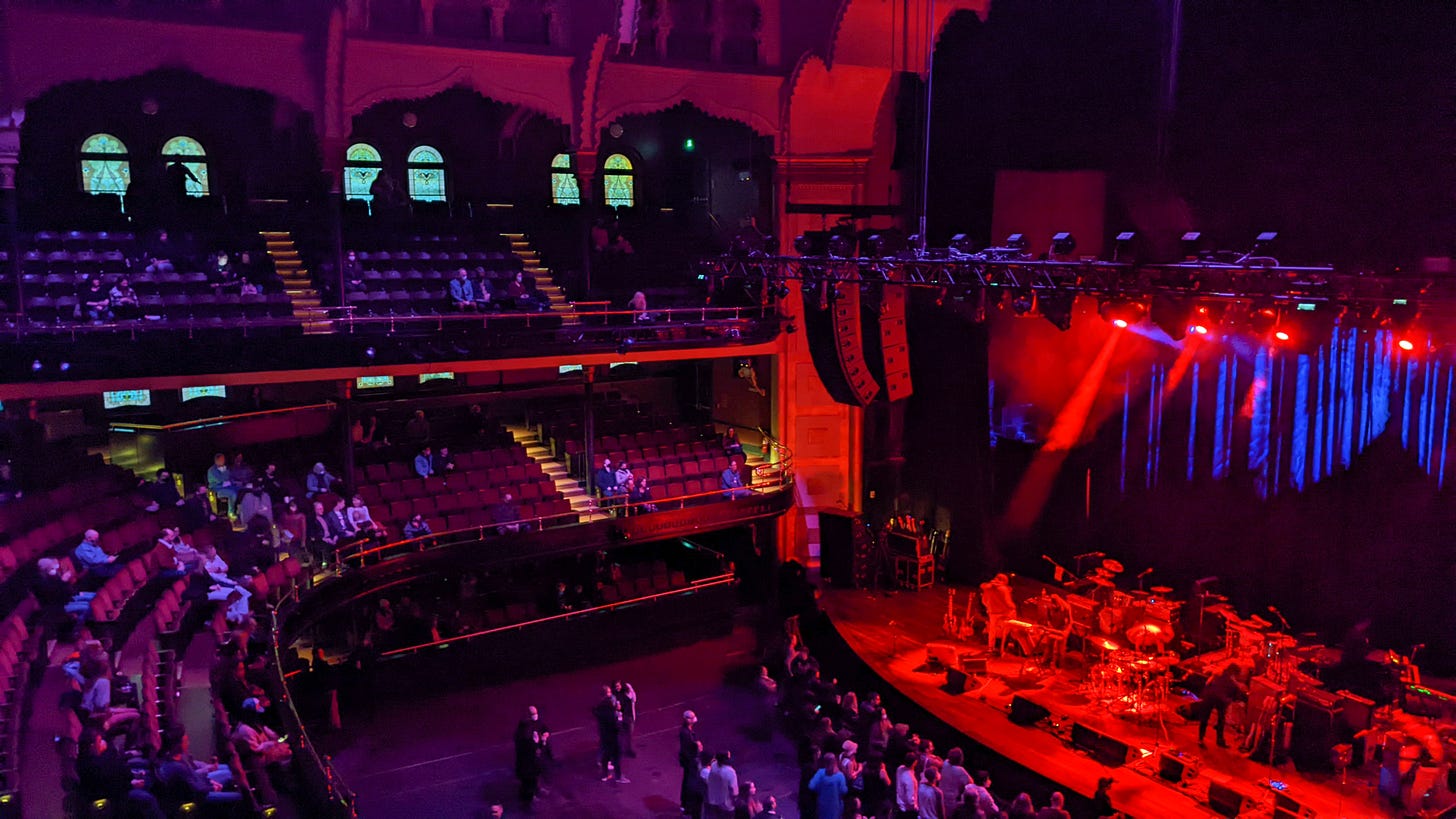

Since the last time I checked in, I got to see three shows over three days consecutively at the new Massey Hall! What a beautiful venue. It’s always been my favourite concert venue in Toronto, but with the renovation, the place has become gorgeous and way more comfortable. I got to see Big Thief and Broken Social Scene twice in a row. I’ll have more to say about those shows later! But let me tell you, Adrianne Lenker is a pro.

Last week, I saw Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022), directed by Daniel Scheinert and Daniel Kwan, who also directed the underrated but genius film Swiss Army Man (2016). It seems like the multiverse thing is in style right now - I wonder if that has anything to do with our present day society. But the main characters are Asian-American and the story is heartwarming, grounded, wacky, sci-fi, and hilarious. Here’s what I wrote on Letterboxd in the lobby of the Cineplex:

A beautiful, emotional film that feels like an action multiverse movie, but is actually a family drama that will be all too familiar for Asian-American families. I did not expect to cry as hard as I did in the theatres. I love the references to Wong Kar-Wai and a certain Pixar film.

I don't think the MCU and Disney can beat this multiverse film, even if it tried.

I also saw The Northman (2022) directed by auteur Robert Eggers. It’s a vikings film and it’s cool. Here’s what I wrote on Letterboxed about the film:

Mythical, dude.

What can I say? I have a way with words. 🤷🏽

Today, I wanted to share a paper I wrote for my PUBPOL 703 Digital Governance class with Professor Tony Porter. You may not know it, but your interactions with the government are increasingly with AI rather than humans. Governments are making significant decisions about people’s lives - whether you receive Employment Insurance or be accepted for asylum as a refugee. It’s important we start to understand the consequences and what we can do about it.

Below is an abridged version of the paper. You can read the full piece by clicking on the title link and going to my blog! Enjoy!

Developing a Canadian Approach to Governing Automated Decision-Making Systems

Written as a paper for PUBPOL703 – Digital Governance with Professors Tony Porter for the McMaster University Master of Public Policy in Digital Society.

Introduction

Algorithms, artificial intelligence (AI), and data predictive analytics are increasingly being used by governments in their decision-making with citizens and immigrants, operating with less-developed or no oversight. The use of AI by the public sector in making government administrative processes more efficient is changing the relationship between the state and individuals. These systems are known as “Automated Decision Making” systems (ADM), which are AI technologies adopted by the public sector “that either assists or replaces the judgement of human decision-makers… us[ing] techniques such as rules-based systems, regression, predictive analytics, machine learning, deep learning, and neural nets.” ADMs hold much promise in improving government service delivery by being more timely and offering easier user experiences. Moreover, they can work faster and more efficiently than humans in performing routine tasks, with the ability to run outside of normal work hours, especially to process large volumes of applications, reduce backlogs, and improve response time. However, particularly when decisions are complex and value-laden, ADMs can have significant concerns regarding transparency, fairness, accountability, due process, public trust, bias and discrimination, privacy, and human rights. ADMs can make flawed decisions based on flawed algorithmic design or flawed data, and, with lack of a clear governance framework, make it difficult for affected individuals to appeal, seek redress, or even know that their application was processed wholly or in part by an algorithm. There is research that found that Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) was using ADM processes as early as 2015 for permanent residency applications through the Express Entry program, Temporary Resident Visa applications from China, and spousal/common-law partner sponsorship applications from Manila, Philippines and New Delhi, India. Research by Petra Molnar and Lex Gill of Citizen Lab and the University of Toronto’s International Human Rights Program conducted an in-depth study on how ADMs used by IRCC and Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) impacted the human rights of immigrants and refugees. Regulation of these processes is beginning to be developed but has yet to catch up to the real impact on people.

Canadian governments are beginning to address the impacts of ADMs. The Canadian Federal Treasury Board Secretariat (“TBS”) issued the Directive on Automated Decision-Making (“Federal Directive”) in 2019. The Federal Directive was one of the earliest examples of regulating ADMs internationally. It has drawn praise for its novel attempt to govern ADMs based on principles of administrative law. However, it has been criticized for gaps in its approach and scope. The Ontario government is also considering the development of a governance framework for AI, through normative principles and guiding documents, as well as the modernization of privacy legislation. However, the Beta principles for the ethical use of AI and data enhanced technologies in Ontario (“Ontario Principles”) and Transparency Guidelines for Data-Driven Technology in Government (“Ontario Guidelines”) are more akin to soft law without proper enforcement mechanisms.

Thus far, there has yet to be a comprehensive, harmonized, and effective Canadian approach to governing ADMs. Building on the initiatives by the federal and Ontario governments, ADM governance needs to go beyond prioritizing the administrative law principles of fairness, accountability, and transparency, but also enshrining principles of justice, human rights and dignity, and building public trust for the public interest. This means strengthening accountability measures by increasing external scrutiny through multi-stakeholder consultations and building effective enforcement mechanisms, expanding the scope of regulation to close loopholes, moving away from a self-reporting survey towards more complete assessments, creating mechanisms for remedies for wrongful decisions, and building stronger responsibilities for ADMs that “significantly affect” an individual.

Challenges

While the Federal Directive and the Ontario Principles and Guidelines are a good start to addressing ADMs, there are still many gaps that prevent these documents from constituting a comprehensive and effective governance framework. Both the Federal Directive and the Ontario documents suffer from a lack of legitimacy, an effective enforceable legal framework, and limited scope. While the Federal Directive was issued by TBS and is thus mandatory and binding on federal government departments, scholar Teresa Scassa argues that “Directives do not create actionable rights for individuals or organizations.” The Directive lacks external accountability, whether Parliamentary or from civil society. Obligations and enforcement are internal. In a similar way, it is unclear where the source of legitimacy is for the Ontario documents and what enforcement mechanisms exist. It is unclear what central agency will be the lead organization in enforcing these principles.

Both the federal and Ontario approaches fail to adequately address how humans fit into the governance framework. This means concerns about how humans interact with their rights as they interact with the technical complexity of ADMs, as well as multi-stakeholder consultation of those most affected.

A large concern about the governance of ADMs is the complex and inaccessible language that makes it difficult for the public to understand the technology and respond to its impacts. It is important then that the Federal Directive mandates that information about the ADM be posted in “plain language.” However, posting the notice at the bottom of the webpage or in a separate link – for example, to a “Frequently Asked Questions” page – might seem more like “checking off the box” to meet legal obligations, rather than providing meaningful notice to individuals about how the ADM will affect them. Additionally, while the Federal Directive mandates that individuals receive a “meaningful explanation” for higher impact level ADMs, it is unclear what counts under this concept. In this author’s experience, a decision maker may provide the bare minimum for written reasons based on template language taken out of context from the individual’s case, rather than a detailed explanation as to why the decision was made. When decisions are significantly affecting an individual through an opaque ADM, it is even more important that meaningful explanations be given to individuals. While the Federal Directive notes that “any applicable recourse options” should be made available to affected individuals, it is unclear what kind of legal remedy – whether it is appeal, human review, judicial review, or other – is available to affected individuals. Lastly, there may be a greater onus on the affected individual to prove the harm and that there are flaws in the algorithm or its data, which is made even more difficult because of the complexity and opaqueness of ADMs, as well as barriers to accessing adequate resources and expertise to conduct the analysis.

In practicality, this creates a barrier to justice. If it is difficult for an individual to access rights to appeal or recourse because of a lack of understanding and a high onus to prove harm, then justice is denied. Moreover, it is marginalized communities and individuals from historically disadvantaged groups – Indigenous people, racialized individuals, people with disabilities, the poor, and queer individuals – that will be the most impacted by ADMs from the beginning of their implementation. Access to justice is already difficult for these marginalized groups, and further obstacles to recourse and “judicial review places an undue burden on individuals to identify and successfully challenge decisions” or even “‘a costly and undue form of punishment.’” With these obstacles, further reform of ADM governance must reconsider recourse avenues, as well as shifting the onus of proof to the operators and developers of the ADM to prove the system is safe and accurate.

For there to be meaningful rights for individuals affected by ADMs, Canadian governments can learn from Article 22 of the European Union’s GDPR which creates “the right not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing.” Additionally, Canadian governments can learn from France's definition of what a meaningful explanation entails.

Full accountability requires a forum for stakeholders to learn, analyze, and scrutinize an ADM. The Federal Directive and the Ontario Principles and Guidelines, while being good first steps, do not constitute effective accountability. The Federal Directive relies on a self-reported survey as an AIA, the nature of which does not meet the standard of an independent, impartial review. Moreover, it is unclear how the Ontario documents will compel parties to commit to transparency and accountability mechanisms. A report by Data & Society entitled “Assembling Accountability” argues “that voluntary commitments to auditing and transparency do not constitute accountability. Such commitments are not ineffectual—they have important effects, but they do not meet the standard of accountability to an external forum.”

For there to be real accountability, particularly to the communities most impacted by potential harms by an ADM, Canadian governments should mandate that ADM operators engage the public and community advocates through multi-stakeholder consultations. There is no avenue for impacted communities to provide feedback about an ADM that can significantly affect their livelihoods. Transparency without an avenue for scrutiny is not accountability.

Next Steps and Conclusion

In developing a comprehensive and effective Canadian approach to governing ADMs, there must be a strong mandate for enforceable accountability and transparency that goes beyond administrative law principles of procedural fairness, but to also uphold justice, human rights, human dignity, and using ADMs for the public interest by building public trust. This starts with a strong source of legitimacy that can mandate effective regulation. On both the federal and Ontario levels, this means going beyond normative principles and guidelines and central agency directives and instead passing legislation. While this may be difficult politically, legislative measures would provide legitimate constraints on government to abide by accountability mechanisms and create legal and actionable rights for affected individuals. To be more effective, ADM regulation must also include “National Security Systems.” Allowing an exemption for these particularly invasive technologies would avoid true accountability for ADMs with the greatest potential for harm, particularly for systems used to surveil, police, or deny asylum seekers refuge. There are procedures that can be put in place to maintain the integrity and confidentiality of “National Security Systems,” while allowing for scrutiny, transparency, and accountability to mitigate risks and minimize adverse outcomes. ADMs must also welcome greater external scrutiny conducted by independent and impartial assessors. It should not be up to a self-reported survey score to determine an appropriate risk and impact level. While this may come with greater operational costs, independent assessments are worth it for additional levels of accountability and transparency. The AIA is not meant just for government to fulfill legal obligations and minimize liability – it is meant to be one (but not the only) tool to hold governments accountable for the extraordinary nature of ADMs and their potential for significant harm.

Federal regulation can also learn from the Ontario Principles by integrating human centric perspectives. In order to build public trust, individuals should know that ADMs are not just being used to make the lives of public servants easier or that it will save money, but that it is for “a clearly articulated public benefit” that is proportional to the additional risk. It is also important to clarify what meaningful explanation means for ADMs and clearly outline avenues for redress and legal remedy that does not put an undue burden on individuals who do not have the expertise or resources to scrutinize an opaque algorithm. A truly effective Canadian approach would be to pursue a multi-stakeholder consultation approach that engages the most affected and vulnerable community groups. This is particularly important with Canada’s commitment to reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, as ADMs can significantly affect their livelihoods. A comprehensive governance document would recognize the disproportionate negative impact that ADMs could have on marginalized communities and historically disadvantaged groups, and that operators of ADMs would commit to working with community leaders to develop these systems, monitor for unintended adverse impacts, and improve their performance throughout their lifecycles.

ADMs need to earn a special level of public trust as their emergence changes the power dynamic and relationship between the state and the individual. Emerging technologies start off as powerful tools, but they can grow to become more integrated in our lives – and not always in beneficial ways. It is important to consider the negative impacts being traded in for potential – even marginal – gains in efficiency. Canadian policymakers have to ask themselves, “Do concerns for large-scale efficiencies and service enhancements justify a mitigation or adjustment of expectations of procedural fairness?” ADMs do not just have individual impacts but systemic issues of justice, particularly affecting already disadvantaged populations. Thus, Canadian governments have to be careful about the use of ADMs and ensure that they are being used responsibly and with the proper safeguards and enforceable mechanisms to prevent harms. At the core of it, a comprehensive and effective Canadian approach to governing ADMs must recognize that “People should always be governed – and perceive to be governed – by people.”

Read the full piece with sources at https://blog.angelogiomateo.ca/blog-post/canadian-approach-governing-adm/

It’s not the hunger revealing

Nor the ricochet in the cave

Nor the hand that is healing